This is part 2 of a 4-part serialization of the first chapter of a book being written by Shaun A. Pennington about the historical and modern-day consequences of sugar that have plagued Virgin Islanders and Americans for 400 years. The excerpts – which have been edited for purposes of this Black history series – paint a grim picture of the ties between slavery’s horrific place in Black history in the Virgin Islands, Caribbean and United States and the nature of the substance that secured slavery as an institution and whose side effects people of color often suffer disproportionately from to this day.

See part 1- Black History: Sugar Slavery in the Virgin Islands

In 1672 an assortment of convicts, prostitutes, indentured servants and Danish West India Co. officials – 190 in all – set sail from Denmark and landed on St. Thomas. One hundred and four of the mixed bag of travelers arrived. Nine escaped, while 77 died on the journey.

In the first year, in a climate ill-suited for northern Europeans, another 75 perished.

It would be nearly a quarter century before the offspring of those original 29 remaining colonists made their way across the island’s mountainous middle peaks to establish the first Danish plantation on St. Thomas’ north side. Jurgen Hansen was one of them. Extensive research by historian David Knight Sr. – who once lived at Eensomhed – reveals Hansen was 20 years old when he claimed the piece of land in an area that for years would be known as Jurgen Hansen’s Bay.

The grounds upon which a smattering of the plantation’s ruins remain roll gracefully from the reconstructed great house above toward a cliff and the seascape beyond. The gently sloping green lawn amidst the surrounding hilly terrain, dotted with white metal tables and chairs from which to enjoy the spectacular view, leaves no telltale marks of the sugar mill that operated in that grass carpeted space 300 years ago.

A large flat area was needed on which to erect the round mill house with additional space to allow the oxen or donkeys to walk endlessly around in a wide circle turning the iron-plated rollers inside the mill that would crush the cane into syrup.

The huge rollers would also mangle the ill-fated slave unlucky enough to get a finger caught in one of the crushers as she pushed the cane through. She would be pulled in along with the stalks and ground to death if she didn’t cut off her arm before it was too late. For that purpose, a sword or machete was kept close by. “If a mill-feeder be catch’t by the finter, his whold body is drwan in and he is squees’d to pieces,” wrote Barbados plantation owner Edward Littleton, as chronicled by Carrie Gibson in her exhaustive examination of the region, “Empire’s Crossroads: A History of the Caribbean from Columbus to the Present Day.”

But the threat of being pulverized was only part of the ever-present danger in sugar production.

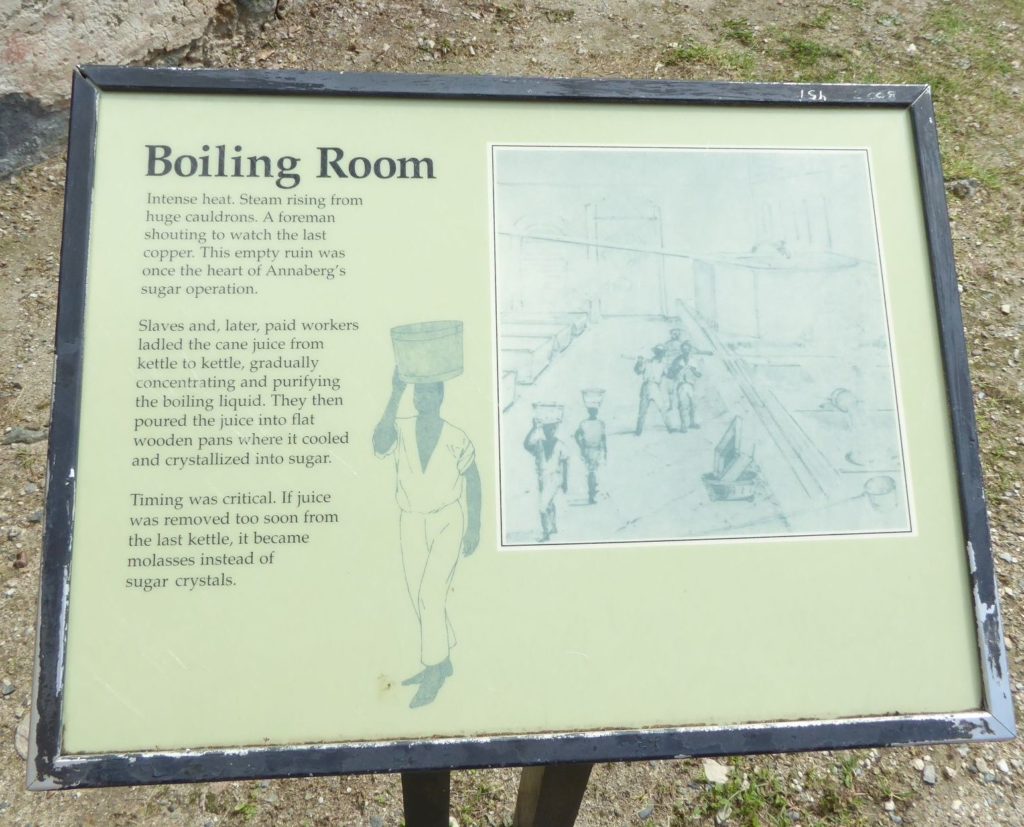

Though ruins of the sugar mill are nowhere apparent, remnants of the next phase of the process, copper pots used for boiling the juice that ran from the mill through wooden troughs to the factory, lean casually against the charming remains of stone walls that crop up from the grass.

In the 1700s, pots full of boiling hot cane juice bubbled nearly around the clock to keep up with the ever-increasing European demand for sugar.

photo)

Along with the hellish heat inside the boiling house, the 212-degree sticky syrup posed its own danger.

As Littleton explained, “If a boyer [boiler] get any part into the scalding suger, it sticks likd glew or birdline and ‘tis hard to save either limb or life.”

Despite being prevented from learning to read or write, many of the enslaved men and women who served the sugar barons of the time had to be and were highly skilled. The boiler, for example, had to know exactly when to pour the juice from one kettle to the next when it was ready. His work led to one precise moment: when the syrup was so thick, and yet clean, that it was time to “strike,” as described in “Sugar Changed the World,” by Marc Aronson and Marina Budhos.

And though historians speculate about the self-esteem of the slaves who were entrusted with the highly skilled jobs, they were still slaves.

Of the original 92-acre estate, 3.3 acres remain of what is left of Eensomhed. But in the heyday of its operation as a sugar plantation, 50 acres were taken up by cane, the planting and harvesting of which came with its own special hell.

The often steep, rocky terrain was leveled for planting by either a team of oxen pulling plows or slaves who worked in the difficult spots, hewing 5-foot square, 5-inch deep areas out of the belligerent land. Then the planting would begin. Slaves were expected to carve out at least 28 of these holes per hour or be beaten by overseers, according to Aronson and Budhos.

Twelve to 14 months after planting, another highly skilled slave had to determine exactly when to cut. Too early or too late by even a few days would undermine the quality of the product.

If life was hard during the planting, harvesting and hauling the cane to the processing plant made those operations look easy.

No matter upon what island or land cane was cultivated, the dangers – and profits – were similar. They included rats, heat, disease and impossible hours that ended in malnourishment and sleep deprivation for the slaves and pots of gold for the planters.

Some claim that the ghosts of those tortured souls yet wander Eensomhed.

“People have seen one in particular,” my friend the owner told me the day I toured the property. But she assured me that in all the years she has lived at Eensomhed, she had never experienced any negative or hostile energy. If the spirits of the slaves remain, they seem hushed.

Perhaps in the 170 or so years since slavery was abolished the winds of change have blown the land’s nightmares away.

Next: How Slaves Lived and Died