Most likely, a lot more Virgin Islanders have health insurance today than did a few years ago, but there are still people willing and able to pay for it who are simply left out of the market.

It’s easy to fall into the gap.

Simply work for a small private company that doesn’t offer group insurance. Or work for one that does offer it and then get laid off when the business downsizes or closes. Retire early — before you are eligible for Medicare — to be a family caregiver or for some other reason. Work part-time at two or three entities that maintain group plans but that don’t cover part-time employees.

Any of those situations could lead you to look for an individual healthcare policy. If you were a resident of a state, you might find the policy is not quite as good as what you used to have. But as a resident of the territory, you won’t find anything. No company offers individual coverage in the Virgin Islands.

Unless you can find a way onto a group plan, you may find yourself going without health screenings and other routine wellness care or even postponing procedures and/or surgery.

The problem and the history

It’s hard to know how many people in the territory are in this position: wanting health insurance but ineligible for Medicare because of age, ineligible for Medicaid because of income, and ineligible for a group policy because of work status.

Most of the people in that gap are between 50 and 64 years of age, according to one industry expert, semi-retired Steve Baker of Baker Magras and Associates. He said the number of people so affected may be no more than 500. But government officials think that is an underestimate.

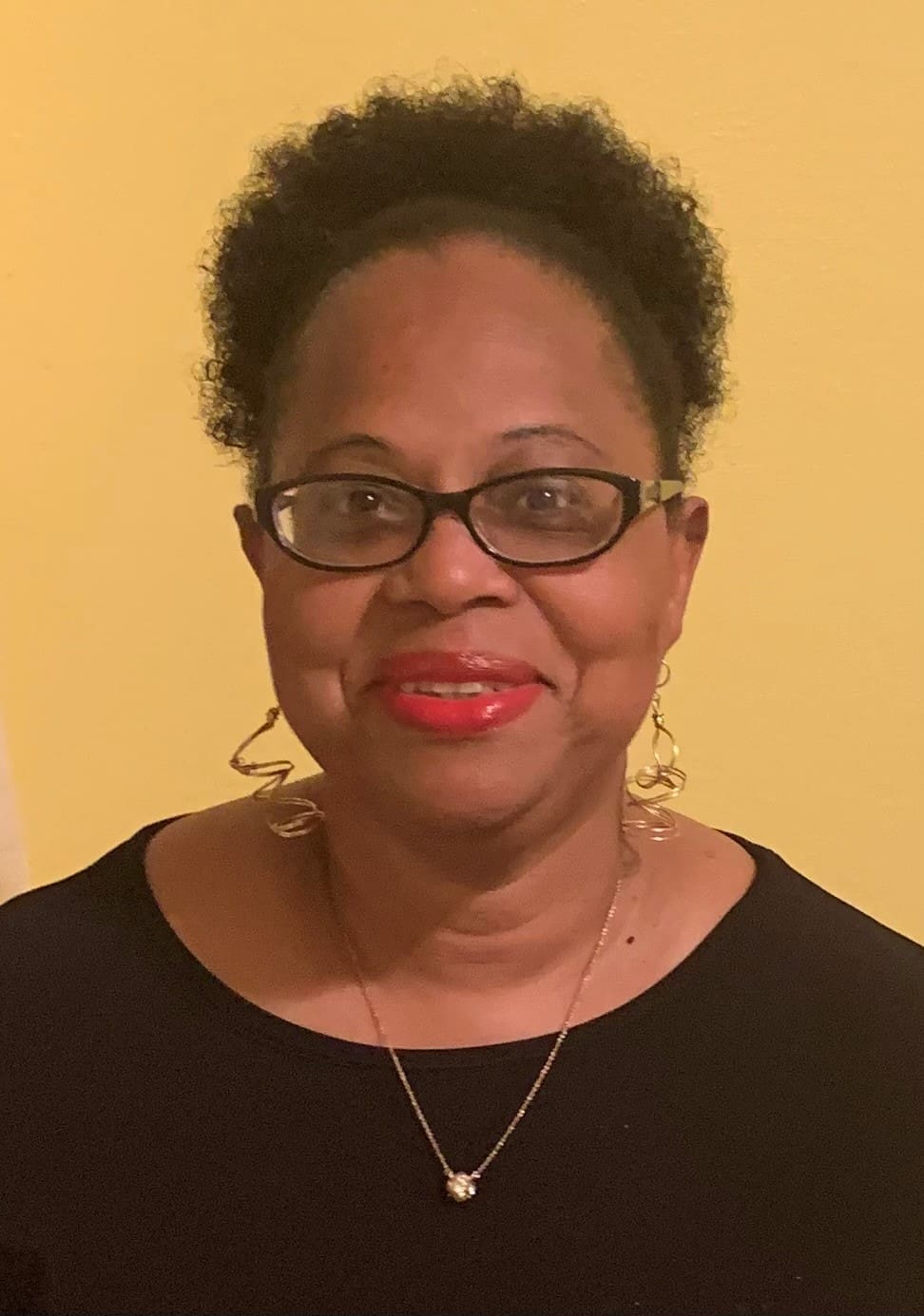

In a joint interview with the Source, Glendina Matthew, acting director of the division of Banking, Insurance and Financial Regulation in the Lt. Governor’s Office, and Cheryl Charleswell, assistant director, both said they believe the number is higher, though neither offered an estimate.

Current numbers for the total number of people who are uninsured are also not available.

A government survey from about a decade ago concluded that roughly 30 percent of the Virgin Islands population (calculated then as 100,000, though the 2020 Census shows a sharp drop in the past 10 years) was living without benefit of health insurance, either by choice or by circumstance.

Matthew said she is unaware of a more recent survey.

“However,” she said, in the past few years, “that number (30 percent) should have significantly decreased due to the expansion of the Medicaid program under the ACA (Affordable Care Act.).” Medicaid provides health care for low-income populations.

That point was also made by former V.I. Delegate to Congress, Donna Christensen, who was in office when the ACA became law and shared her recollections and insights in an interview.

Supposedly about 30,000 people in the territory were without health insurance coverage at the time the ACA was being debated, she said. Since passage of the federal law, with its liberalization of Medicaid for the territories, about 20,000 people have been added to the Medicaid program in the Virgin Islands. That means they have health coverage.

“A lot of people blame this (the lack of individual coverage) on the ACA,” she said as if the territory chose Medicaid expansion over full participation in ACA.

“We fought hard to be part of the ACA,” she said, but state-like participation was never an option. The Medicaid expansion was a great compensation, but it wasn’t a matter of choosing it over full participation.

Some industry experts say other factors dissuade insurance companies from getting into the V.I. market, especially the individual policy market. The small population of the territory is a disincentive for a business that relies on large numbers for success. And the relatively high rate of some diseases also makes the V.I. market unattractive.

Is there a fix?

Matthew and Charleswell said their office is currently in negotiations with an insurance company about the possibility of it offering individual coverage in the territory. They declined to name the company.

But there have been similar negotiations in the past that didn’t bear fruit.

Some companies aren’t interested in the territory because it doesn’t have a mandate, Charleswell said, referring to the idea of a government requiring that everyone have health insurance. Companies need assurance that there will be a sufficient number of clients to cover the cost of the business.

The mandate was an integral part of the ACA, but it was effectively eliminated in 2019 when Congress stripped away the tax penalty for failing to carry health insurance.

Since then, five states and the District of Columbia have passed laws requiring residents to acquire health insurance. D.C.’s law makes exceptions for those who can’t afford insurance and penalizes those who can afford it but don’t acquire it. Massachusetts, New Jersey, Vermont, California, and Rhode Island all have laws that financially penalize individuals who can afford coverage but fail to acquire it. They also offer subsidies to persons who cannot afford insurance.

A few years ago, Baker thought a local mandate might be the solution, but he says now he doesn’t believe it would be enforceable.

The question of whether to implement a mandate is a policy question that Matthew declined to discuss.

“But remember that a mandate can’t stand without subsidies,” she said, and the V.I. government can’t really afford to pay subsidies.

There are other factors that make it tricky to negotiate with a company for individual coverage.

The government wants to protect the potential clients, Matthew said. They want to be sure the company is viable and will offer insurance at rates that are reasonable and that coverage will benefit the people who obtain it.

For instance, Matthew said a company must agree to offer coverage for hypertension, diabetes, and coronary heart disease – all three of which are common problems in the general VI population. They can’t exclude someone from coverage just because they have one of those conditions, “although we know some persons may still be excluded on an individual basis,” she said.

“It’s a balancing act for us,” she added.

Officials have tried to address the lack of individual coverage along with virtually every insurance-related issue in a comprehensive overhaul of existing law. The Virgin Islands Health Reform Act was drafted in 2015. It can be found on the Lt. Governor’s Office website under the division of Banking, Insurance, and Financial Regulation. But the Legislature hasn’t taken it up.

“It hasn’t gotten much traction,” Matthew said.

The bill may or may not have made much difference to the individual insurance market, given the reluctance of many companies to offer it.

Short of luring an insurance company to offer individual coverage in the territory, there are some strategies that may work for some people.

The administration is encouraging business-related entities such as a chamber of commerce to offer a group health insurance policy to its members. That could pick up businesses too small to qualify for their own plans and possibly some self-employed individuals.

Baker had several suggestions:

*For those who can, claim residency in a state rather than in the territory and get into an insurance exchange in that state.

* Take advantage of COBRA – the federal law that allows an individual to pay the full cost of a premium and retain coverage under a group plan for 18 months (or, in some cases, for 36 months) after losing a job with a group plan.

* Incorporate or form a limited liability company with another individual (even a spouse) and get insurance through that company. (Banking, Insurance, and Financial Regulation does not recommend that approach.)

Baker also suggested that the government raise the age limit for children to stay on a parent’s policy to 30 years.

“That would help people,” he said. “Pass that law. Most states have.”

Christensen suggested the government could try for what is called an 1115 waiver, a relatively new program of the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services that, under specific circumstances, allows a jurisdiction to use Medicaid funds to subsidize health insurance for certain residents.

That may or may not work, but she had another, more immediate suggestion for individuals struggling without insurance: Make use of the territory’s two private healthcare entities — the St. Thomas East End Medical Center, which serves both St. Thomas and St. John, and Frederiksted Health Care Inc. with outlets in Christiansted, Sion Farm and Frederiksted (a.k.a. the Ingeborg Nesbitt Clinic) on St. Croix.

Both organizations are designated as Federally Qualified Health Centers, and both offer primary care at rates on a sliding scale. “You pay based on family size and income,” Christensen said.

While suggestions for ameliorating the situation abound, there’s no obvious panacea on the horizon. Meanwhile, anecdotes continue to circulate. A woman gets married so she can qualify for her new husband’s health plan; a man postpones a much-needed surgery for a year until he reaches age 65 when he qualifies for Medicare; for many, annual check-ups and regular health screenings become a thing of the past.