The outlook for coral reefs continues to dim worldwide, and regionally, the situation is particularly dire.

Already rapidly degrading from bleaching events, from the mysterious pathogen of Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease, and from various human-development stresses, Caribbean reefs are now exploding with algae crusts that threaten to muscle out live coral.

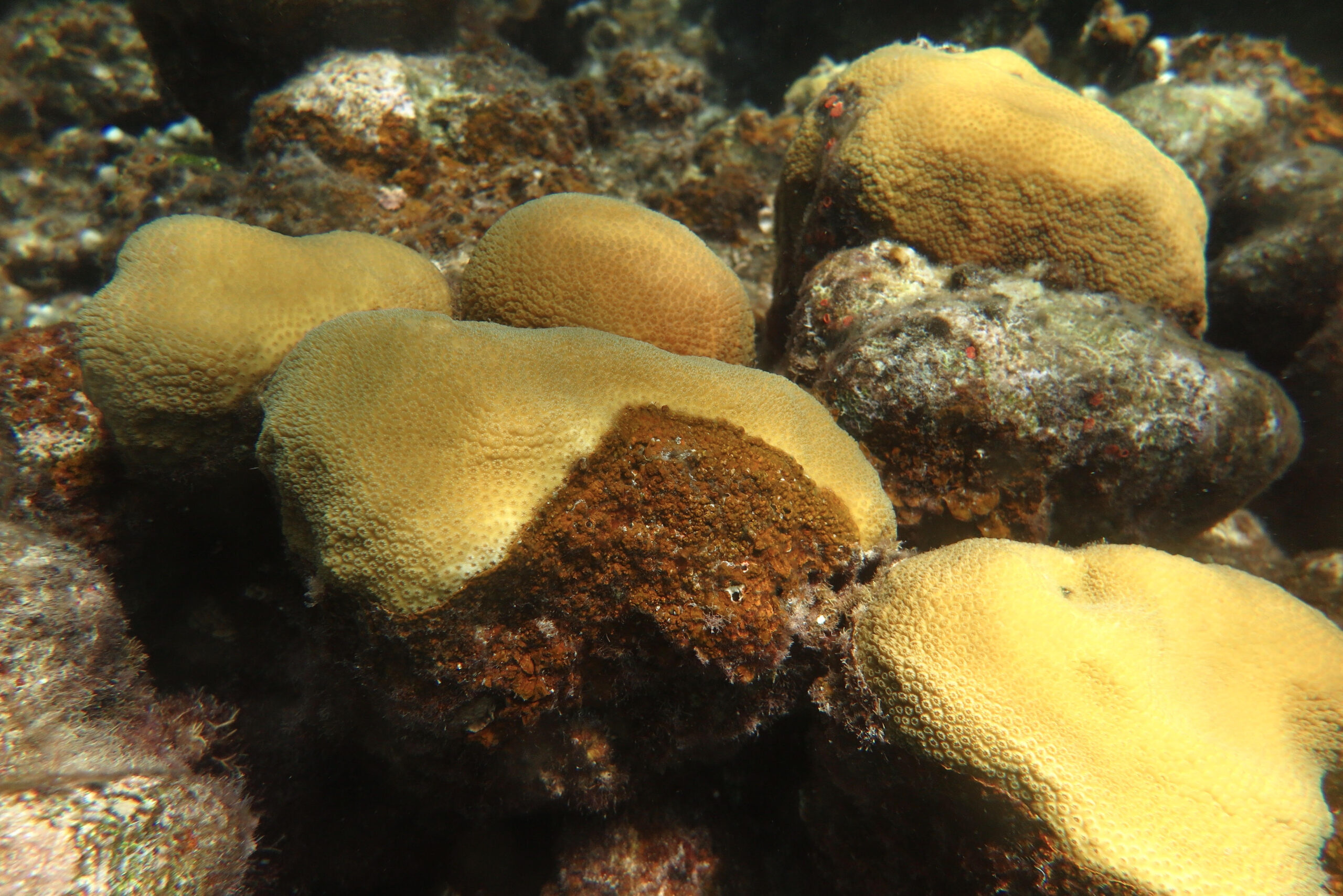

So-called PAC (peyssonnelid algal crusts) are not a new phenomenon. Marine scientists have long been aware of their negative impact on coral reefs, where they compete for space and nutrients with coral. What is new is the speed at which PAC are overtaking corals in some parts of the world, including the Caribbean.

In a research paper entitled “The Rising Threat of Peyssonnelioid Algal Crusts on Coral Reefs,” published earlier this month in the peer-reviewed publication Cell, the authors suggest that PAC “could hasten the global demise of corals on reefs under accelerating climate change.”

The paper is the work of three researchers: Peter Edmunds of California State University, Thomas Schils of the University of Guam, and Bryan Wilson of the University of Oxford, United Kingdom.

Their findings dovetail with local research, according to Tyler Smith, a University of the Virgin Islands professor and the director of the territory’s coral reef monitoring program.

The local program tracks 34 reefs throughout the territory, in depths ranging from about seven feet to 220 feet, he said.

Smith said that one author of the recent report, Edmunds, has been studying reefs in St. John waters for about 40 years.

“PAC became conspicuous on the reefs of St. John, United States Virgin Islands, around 2012, and by 2019 they covered 47 percent to 64 percent of benthic space (ocean bottom) at three-meters depth,” the paper states.

“We really noticed it about 2016 or 2017,” Smith said. It prompted the V.I. researchers to look back at video records they had from previous surveys, and sure enough, they were able to spot a small amount of PAC that had previously been overlooked. The damaging algae crusts have been on St. John reefs “since at least 2004.”

PAC is easily mistaken for other types of algae, according to the report.

That’s one reason it is unclear whether the current prevalence of it on Caribbean reefs indicates an ecological change that has caused PAC production to rapidly accelerate or whether it is an invasive species that is multiplying rapidly because it has few predators in this area.

“Maybe we’re just seeing it more,” Smith said. Or maybe it hitched a ride on a vessel coming from the Indo-Pacific, where it has long been established.

Either way, controlling PAC is not going to be easy. Smith cited two UVI research projects that showed it is highly resilient.

One study conducted by Karli Hollister in 2018 found that only one in six coral species studied was able to stop the advance of PAC.

In a follow-up study, another UVI student, Alexys Long, tested the effect of providing extra nutrients to PAC. There was virtually no change, indicating that the algal crust already gets all the food it needs. Long also introduced some PAC to what may be their only serious predator in the Caribbean, the black spiny sea urchin, and showed “it took very high numbers” of sea urchins to control the spread of PAC.

Unfortunately, as the authors of the Cell report noted, the sea urchin is still recovering from a “population collapse” a few years ago.

Smith said there is an ongoing project in Puerto Rico to “grow” sea urchins that could prove useful.

Short of a massive effort to physically remove PAC – obviously an impractical undertaking except in a small, confined space – there apparently is little other method of intervention.

Smith said he leans towards the idea that PAC is an invasive species. If so, “eventually, natural controls will kick in.”

He also noted that although PAC has rapidly become pervasive, “It’s not taking over everywhere.” It tends to favor reefs in clear water where there is a lot of wave action.

Meanwhile, there are still other coral problems to worry about.

Record water temperatures at the end of the summer translated into a 2023 bleaching event that rivals that of 2005, Smith said. The event 18 years ago weakened a massive amount of the V.I. coral population and more than half of them died from resultant disease.

It’s too soon to know how this year’s bleached coral will fair in the aftermath of the event, Smith said, but added, “We do expect a lot of morbidity.” We’ll know the extent in early 2024 when reef surveys are conducted.

Last spring, a report on Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease co-authored by another UVI professor, Marilyn Brandt, underscored the dangers facing coral reefs: Since the 1970s, there has been a decline of between 50 percent to 80 percent of living coral tissue.

The lush Caribbean reefs of the 1980s are gone, Smith said.

It was their beauty that lured him into the field of marine science, he said, adding with dark humor, “I didn’t expect to be a coroner or a hospice nurse.”