It’s about 2 a.m. in the morning and while most may be asleep, the crew for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Hurricane Hunters are at Bohlke International Aviation on St. Croix, preparing to fly straight into Hurricane Lee, which on Tuesday was a disorganized Category 3, potentially 4 hurricane. The team was so gracious to allow the Source to tag along on their sixth flight of this series.

At around 2:30 a.m., the team began their first briefing with Flight Director Quinn Kalen, who provided an update on the storm, its track, six-hour flight time that usually can last from eight to 10 hours, their plans of penetrating the storm three times, weather conditions and more.

After the briefing, the team then headed next door to the Henry E. Rohlsen Airport by vehicle, where their airplane, a NOAA WP-3D Orion N43RF, also known as NOAA43 and “Miss Piggy,” awaited their arrival. NOAA also operates another aircraft by the name of “Kermit,” which functions just like Miss Piggy. These aircraft are large, four-engine, propeller-driven planes equipped with nose, belly (lower fuselage) and tail radars. Both aircraft have a variety of meteorological and oceanographic instruments to gather data in and around the storm.

What’s so unique about this 43-year-old aircraft and this flight is not only has it flown through catastrophic Hurricane Hugo that devastated St. Croix in 1989, but it flies directly into the storm. Other aircraft fly above and around to collect data but this aircraft goes straight into the hurricane, feeling the outer bands of the storm, experiencing the calm eye and right back into the storm again.

Prior to boarding the plane, from a distance, the aircraft looks like an average passenger airplane, but as you approach it, you can visibly see the exterior is equipped with high-quality equipment and tiny hurricane symbols and the year of every storm it’s flown through.

As you board Miss Piggy, the interior looks like a flying command center out of a sci-fi movie. With desk stations, computers, instruments, and a break area, this aircraft is equipped and ready for the mission ahead. Final safety briefings and updates from Kalen were provided to the crew of 20 people, and the passengers were on the way.

At first, the flight was smooth, encountering minor bumps and within the hour, as expected, the first set of bumps began signaling we were approaching the storm. The best way to describe the turbulence is like being in the ocean with rough seas. The plane went up and down with force. Prior to taking off, there was mention of potential air sickness given the bumps. The pilots, however, maneuvered the aircraft with great skill for most of the flight, which can speak for their professionalism. They provided moment-by-moment information over a headset radio as turbulence was about to occur.

Scientists also communicated over the radio when they saw great opportunity to drop the larger tubes out of an exit hole from the aircraft called Airborne Expendable Bathythermographs, or AXBTs, which measure ocean temperature from the surface to about 400mm. These instruments are transmitting pressure, humidity, temperature, and wind direction and speed as they fall toward the sea, providing a detailed look at the structure of the storm and its intensity. As the hatch opens, you could feel the pressure of the outside rush to your ears.

They also use smaller Pringle can-sized testing instruments called dropsondes which measure air temperature, pressure, humidity, wind speed and direction.

The scientists communicated with the pilots when they felt enough data were collected. Scientist Dr. Sim Aberson mostly spoke to the pilots on the flight, who were Aircraft Commander Lt. Cmdr. Brett Copare, NOAA Corps, and Co-Pilot Lt. Cmdr. David Keith, NOAA Corps, and Co-Pilot Lt. Chris Wood, NOAA Corps. They also communicated by a group chat on computers on the plane.

Scientists on the ground were able to communicate with scientists on the plane. The National Hurricane Center was also able to receive whatever data were received from the drops in real time.

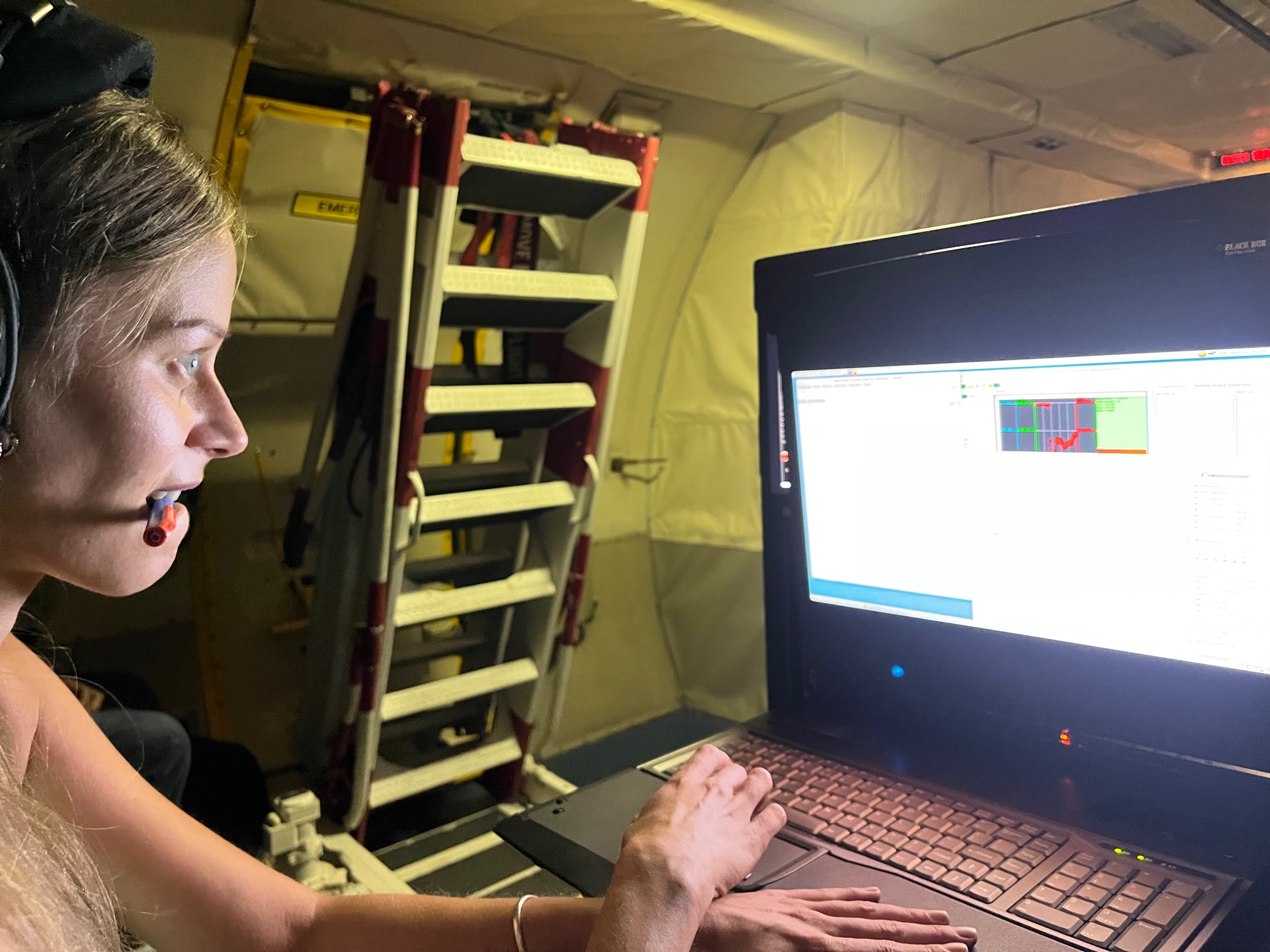

Scientist Kelly Ryan shared with us a little bit of what she was specifically looking for, monitoring her computer closely for wind speeds and comparing it closely to the data collected by the Air Force earlier that day. “The combination of these things is where in the storm I may be interested in collecting more measurements,” said Ryan. Keep in mind that the scientists onboard only collect the data while those receiving the data at the National Hurricane Center interpret and determine the track of the storm, the category, etc.

The method approach we used on this mission was a standard TDR Butterfly, which consisted of three penetrations into the storm and into the eye. The toughest part is getting to the eye in wind bands of up to 90-plus miles per hour, but once in the eye of the storm, it is a whole other experience.

The one word to describe the eye is “peace,” as though the hurricane didn’t even exist. Lee’s eyewall on Tuesday was not defined, so you were not able to see a very clear eye wall. However, the peaceful experience of the inner eye was there. You could now clearly see the sky and look down into the ocean of choppy, rough seas.

While entering and leaving the bands, we encountered heavy rains, extreme turbulence at times and not being able to see outside of the plane. The entire experience is truly a ride you will never forget. After entering the storm twice, the crew took a 15-minute break and entered one last time. Once completed, the pilots flew back to St.Croix. It was another successful mission where information was transmitted to the National Hurricane Center and from there to the media so that updates can be communicated in case a hurricane were to head in the listening public’s direction.

The crew’s rest day was scheduled for Wednesday and their plans of picking it right back up early Thursday at 2 a.m. will begin again. The flights also occur at 2 p.m. Lee is not expected to make landfall, so the crew can leave, but they may be back next week, giving the status of two more systems in the Atlantic.

The NOAA Hurricane Hunters typically fly during hurricane season (June 1–Nov. 30), depending on the number of storms, so it is difficult to say how many times they fly per season.