I have a couple of speaking engagements for this Black History Month. Someone might ask, why study Black history? For one thing, those of us who are descended from what is termed as Negroid, the history of Black people didn’t start from the importation of enslaved Africans to the Western Hemisphere. Nor did the history of man start with the cartoon show of Fred Flintstone. Scientists have been telling us for some years now that human life began in Africa. But there are other reasons we all should study Black history.

Many of the great contributions that Black people have made to the world have been misunderstood, misinterpreted, and misrepresented over the years. For example, ancient Rome was still a village when ancient Egypt had been flourishing for thousands of years. Rome began to emerge as a large civilization during the time when Egypt began to decline. Before the rise of modern Europe, ancient Egypt had existed for thousands of years.

It was after 1,000 years of Egypt’s glory that the Franks, Vandals, and Goths began forming an alliance in what we know today as Europe. Much later, in the 11th century A.D., the warlike Franks banded together to form what is known as France toady. The Greeks learned in the schools of ancient Egypt. Ancient Egypt had developed a religious system called Mysteries, whereby the first system of salvation was formed.

According to Dr. George G.M. James’ book, titled “Stolen Legacy,” “After nearly five thousand years of prohibition against the Greeks, they were permitted to enter Egypt for the purpose of their education.” The Greeks learned from the ancient Egyptian priests the arts, sciences, and philosophies of life. James stated that through the Persian invasion and then later through the invasion led by Alexander the Great, the Greeks learned all they could of the culture and history of ancient Egyptians.

We should know in world history that Alexander the Great ravaged the royal temples and libraries of ancient Egypt. The books were stolen from Egypt and Aristotle converted the books into his school, the Library of Alexandria. The large number of books ascribed to Aristotle were the ancient Egyptians’ property.

James further stated, “The history of Aristotle’s life has done him far more harm than good, since it carefully avoids any statement relating to his visit to Egypt, either on his own account or in company with Alexander the Great, when he invaded Egypt.” In 322 B.C., Aristotle died. But before his death he secured, with the help of Alexander the Great, a large quantity of scientific books from the royal libraries and temples of Egypt. Thus, the science and technology that created today’s modern world was the knowledge of Black people and not of the Greeks, as they would have us believe.

In history, we learned how Columbus explored the Western Hemisphere. But before Columbus encountered the West, the Africans were already in ancient America. In fact, there were Africans, not as slaves, that accompanied Columbus on his voyage to the so-called New World. According to Black Fact 365, “The Olmecs were ancient Africans who travelled to the Americas over 1,000 years before Columbus.”

Nevertheless, let us bring Black history closer to Virgin Islands history. The first free Black man to arrive in Borinquen, known today as Puerto Rico, in 1509 was Juan Garrido. According to historians, he was the son of an African, and joined Ponce de Leon to explore Puerto Rico. Garrido, a high-ranking official in Ponce de Leon’s military, also landed on St. Croix (Ay-Ay) in the search for “Island Caribs” during the 1500s.

However, Garrido was not the first African to set foot in the West Indies. Africans traded with the Amerindians of the West Indies, South and Central America as well as North America for hundreds of years before the first Europeans entered the West. When I attended my daughter’s graduation at Florida A&M University in 2008, I visited the campus Black Museum. At one of the exhibits, there were artifacts of Africans’ presence in North America over 2,000 years ago.

In the mid-1990s, I attended a scientific conference in Honduras. As part of the meetings, we visited one of the historic sites of the country. Here again, the tour guides pointed out to us the presence of Africans for thousands of years in this region of the world. The pyramids of the historic site were influenced by the architecture of the Africans that once traded with Native Americans in this region.

In 1975, a team of professionals from the Smithsonian Institution reported on the two findings of Negroid male skeletons in a grave site near Hull Bay beach on the northwestern side of St. Thomas. According to the late Professor Ivan Van Sertima’s book, titled “They Came Before Columbus,” in reference to the grave site on St. Thomas, “This grave had been used and abandoned by the Caribs long before the coming of Columbus. Soil from the earth layers in which the skeletons were found was dated to A.D. 1520.”

It was reported also of this finding in Hull Bay that around the wrist of one of the skeletons was “a clay vessel of pre-Columbian Indian design.” As well, studies were done on the skeletons’ teeth that showed “dental mutilation characteristic of early African cultures.” From St. Thomas to St. John, we step into Black history again. In 1971, I was still in grammar school when Michael Cudjoe, a young ambassador from Ghana, accompanied a fifth-grade class on a hike to Reef Bay Valley on St. John to examine the petroglyphs.

Cudjoe recognized the carvings on the rocks below Reef Bay Falls because he had seen carvings like them back home in Ghana. According to Cudjoe, the carvings are Ashanti symbols, one meaning “Accept God.” The theory is that the petroglyphs were the works of African artists.

Bruno Adriani, an Amerindian art historian and author of “Pre-Columbian Sculpture-Olmec to Huastec,” also supported Cudjoe’s claims that the petroglyphs are of African design and not Indian. Ivan Van Sertima, professor in linguistics and anthropology also identified some of the carvings as African.

Why not study Back history?

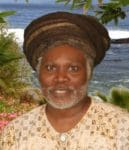

Olasee Davis is an Extension Professor/Extension Specialist in Natural Resources at the University of the Virgin Islands who writes about the culture, history, ecology and environment of the Virgin Islands when he is not leading hiking tours of the wild places and spaces of St. Croix and beyond.