The League of Women Voters of the Virgin Islands hosted Planning and Natural Resources Commissioner Jean-Pierre Oriol in a wide-ranging discussion Saturday on a variety of topics, but the explosion of charter boats in the territory since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic — particularly in Magens Bay and the St. Thomas Harbor — stirred the most comment and concern.

Gov. Albert Bryan Jr.’s administration began in 2019 with a goal of expanding the marine economy as an “untapped market,” said Oriol. What officials did not expect was the advent of a worldwide pandemic in March 2020 that closed most neighboring borders, including the British Virgin Islands, and catapulted the U.S. Virgin Islands to the top of an industry that had been dominated by the BVI.

Businesses such as The Moorings, a luxury charter company that had been based in the BVI, relocated to Yacht Haven Grande on St. Thomas in January 2021 and has since decided to stay, said Oriol.

“That accelerated where we were” in terms of the charter industry, he said.

Enter the Virgin Islands Professional Charter Association, or VIPCA, a nonprofit that represents the charter industry. In 2020 it approached the Bryan administration about the infrastructure needed to help responsibly expand the industry, including overnight moorings, said Oriol. At the time the BVI had more than 600 and the USVI just 14, he said.

In March 2021, with more than 200 new vessels registered to DPNR since the start of the pandemic one year earlier, the V.I. Legislature approved VIPCA’s plans to install and manage 100 helix-type anchored moorings across the territory to sustain the demand for transient vessels — those staying overnight — and to protect the marine environment from anchoring, which can destroy grassy seabeds and coral.

In September, the territory doubled that number to 200 moorings in a public-private partnership with VIPCA.

The project “will substantially reduce potential damage to our coral reefs, offering a safer and more convenient alternative to anchoring for both our residents and visitors,” Bryan said at the time. “We can now extend a warm welcome to a diverse range of vessels, including monohulls, multihulls, and mega yachts, in our beloved bays with utmost ease.”

One of those locations is Magens Bay, where VIPCA has proposed six day-use and nine transient moorings, said Oriol, while acknowledging that “there are people who believe that Magens Bay shouldn’t have any vessels whatsoever.”

However, the bay is a legal anchorage, he said, and until a law is passed designating it otherwise, “we want to manage whatever will happen.”

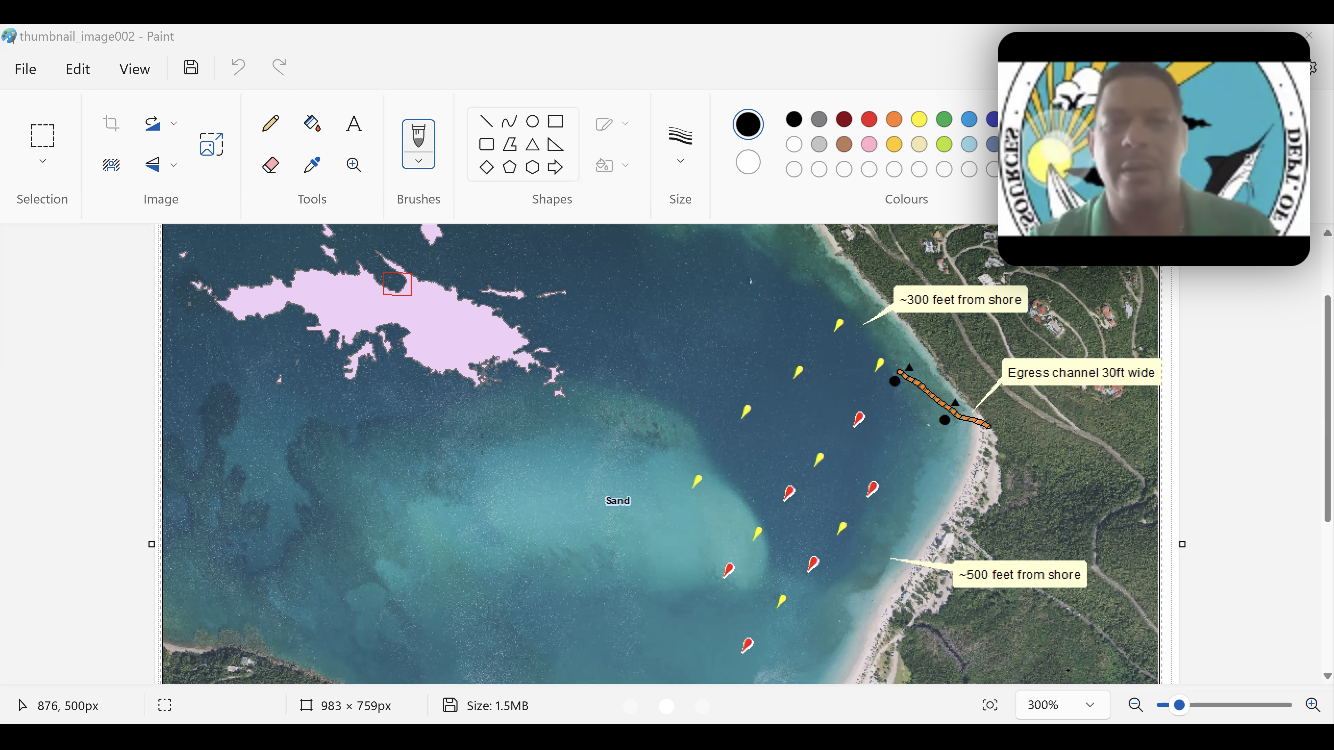

The proposed layout would place the moorings some 500 feet offshore, about 250 feet past the swim buoys, and would alternate between transient and day use, so that boats cannot raft up and so that overnight vessels have room to swing in the current, said Oriol. The latter would be limited to three days and monitored by VIPCA, which has developed an app to track users, he said.

The focus of the plan is to reduce harm to the marine environment, said Oriol, who estimated that the sea grass and live coral in Magens Bay has “gone down significantly in the last 30 years,” mainly due to sediment runoff from the widespread development of Estate Lerkenlund above the bay and Peterborg, the peninsula that hugs its east side.

However, some at Saturday’s meeting, moderated by league president Dr. Gwen-Marie Moolenaar, questioned the impact of massive yachts on the humans who use the park, too.

While she understands the USVI is a tourism economy and that incomes must be made, “I think you’re missing something. I think you’re missing the impact on people,” said Felicita Richards, who lives up the hill from Magens Bay and makes daily visits to the park that Arthur Fairchild deeded to the people of the Virgin Islands in 1946. “We see things going on that your office cannot see,” she said, echoing the concerns of others who spoke up at the meeting.

“When you drive in the downtown area of St. Thomas you cannot see past the boats to see the harbor of St. Thomas. When you are on Magens Bay you cannot enter the water of Magens Bay without having to be in the backyard of somebody’s boat. These things have a psychological and a social impact on the population of the Virgin Islands and I think you are missing these concerns,” said Richards.

“How are you getting additional input from the public regarding the moorings in Magens Bay and the St. Thomas Harbor?” she asked. “It’s not just an economic impact, it’s not just the natural resources impact — there’s a psychological and social impact as well that is being overlooked and neglected.”

Under V.I. Code, the St. Thomas Harbor is among 16 sites designated as mooring and anchoring areas for the Virgin Islands since the 1980s, said Oriol, and set aside for that purpose. “It’s a harbor. It’s a commercial space. It is the center of the marine industry here in the territory” and the industrial hub, and during the winter tourist season it is home to some 400 vessels, he said.

Regarding Magens Bay, nothing is currently set in stone, he said. “The idea for us is that with any passage of that plan, what we see right now [with boats helter-skelter] would not happen because this would be the way we are going to limit the area to 15” vessels, he said.

Additionally, a town hall will be held to discuss the Magens Bay proposal, he said. Two were held for Round Bay on the far East End of St. John, where boating also has proved controversial, including one resident couple that sued DPNR over its management of the area.

“Right now, there is no legislation that would not allow for somebody to anchor inside of Magens Bay. You mentioned persons being in the backyard of these vessels — we’re talking 500 feet offshore. That’s in 10 to 12 feet of water. The swim area is put out around 200 to 220 feet offshore in about nine feet of water because most of the swimming population and activities don’t take place in the deep,” he said.

“What the department is trying to do, because there is no prohibition right now, is to find a happy balance,” said Oriol, who added that “to me, 500 feet is a pretty good distance” for moorings to be placed from shore. “At the same time, we recognize that there are those that don’t want any vessels to be at Magens. I recognize that,” he said.

That includes former Sen. Ruby Simmonds Esannason, who also served the territory as Education commissioner.

“I am one of those people and I am going to fight however we have to, through legislation or whatever” to keep boats out of Magens Bay, she said. “We have to have some place that is protected and sacred for the people. You talk about looking at the sea grass and looking at things in the environment but not so much about the impact on the people. It is the people who are important, and we are the ones being impacted,” said Simmonds Esannason.

“I know the government wants to make money, but we have to look out for the people. I think Magens Bay needs to be a designated sanctuary for the people of the Virgin Islands,” she said.

“As was the goal of the philanthropist who gave it to us,” said Moolenaar.