Editor’s note: This is the third in a three-part series about the indigenous people who lived in the Virgin Islands prior to European conquest. Read Part 1 here, and Part 2 here.

In 1990, pre-Columbian artifacts found during the initial phase of construction at the Tutu Park Mall sent experts scrambling to survey the site before it was covered in concrete.

Twenty-three years later, a portion of the roadway near Market Square in downtown St. Thomas was torn up to replace a waterline, revealing an array of artifacts left by people who lived there at least 16 centuries ago.

Fortunately, the 2013 downtown discovery was subject to a set of laws and protocols for archaeological discoveries, and a team of archaeologists was quickly mustered.

Since the road project was federally funded, it triggered a compliance process involving the National Park Service and the Virgin Islands State Historic Preservation Office (the division of the Department of Planning and Natural Resources locally known as VISHPO).

During a three-week excavation in 2014, a dozen archaeologists and dozens of volunteers collected 85 cases of artifacts made of shell, stone and ceramics. These objects were found, made (or traded) by the Saladoid people, the ancestors of the Taino people who dwelled in these islands when Columbus first sailed through in 1493.

“Only a portion of the site was exposed in the street, of course, and it was a portion that consisted of refuse heaps,” said archaeologist Emily Lundberg, who worked on the project. “The rest of the village must lie underneath the adjacent buildings and streets.”

The excavated portion was radiocarbon dated to the period of A.D. 300-500, Lundberg continued. “It represents a phase of the Saladoid era that had previously been unknown on St. Thomas. No other pre-Columbian culture was represented, although historic-period and modern material lay above. It seems to me fantastically lucky that a strip of these deposits remained intact right under Kronprindsens Gade, unscathed between major pipelines. One just never knows what can still be found, even in highly developed places.”

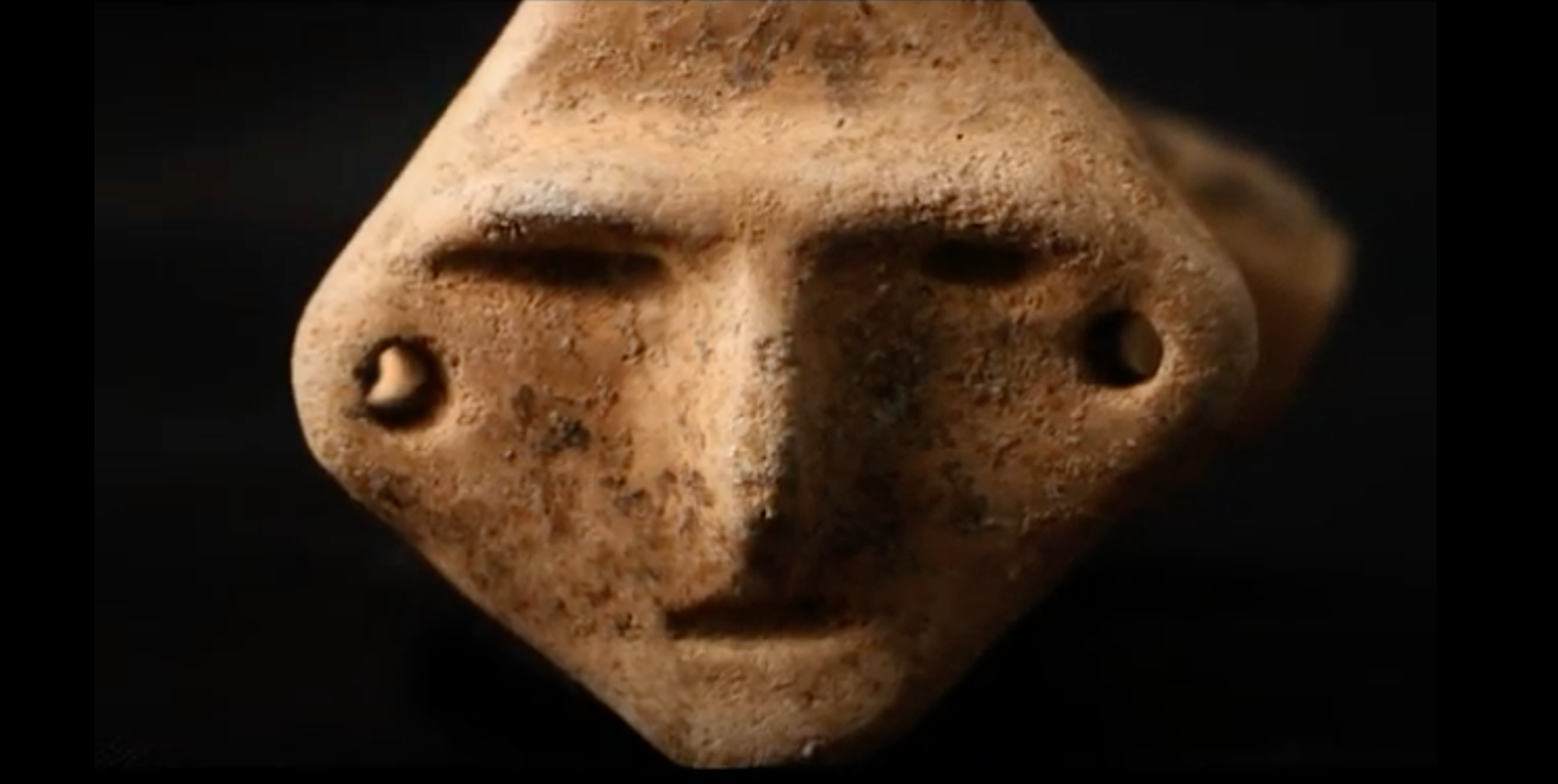

The collection of retrieved objects included thousands of shells and bones from food consumed, as well as examples of finely made pottery, stone tools that could be used for farming, cooking and shelter making, and objects with spiritual significance, often represented by animals.

One of the most surprising objects found was a red bead made of carnelian, a semi-precious gemstone not found in the Virgin Islands. Principal investigator David Hayes speculated that the Saladoid people traded throughout the Caribbean and maybe interacted with people as far away as South America and Central America.

Unfortunately, there is nowhere you can go to see these objects in person. They are not on display on any of our islands — in spite of the best intentions of the staff of the Historic Preservation Office.

Why aren’t these artifacts available to the public? The many reasons are given below, but for those who want to see what the artifacts look like now, there is an excellent video recording available online.

The Charlotte Amalie Saladoid Excavation is posted on YouTube (VISHPO also has DVDs) thanks to efforts by the St. Thomas Historical Trust, VISHPO, and the National Park Service. Produced by Erik Miles and filmed by William Stelzer, the video includes close-up photography of the objects and discussion of the people who left them behind.

As for the artifacts collected during excavation of the Tutu Park Mall site, there was originally much talk about putting them on display at the mall, but it soon became clear that their security in a public, commercial space couldn’t be guaranteed.

Later, when renovations were completed for the Fort Christian National Historic Site in Charlotte Amalie, some people suggested presenting the collection there. However, Sean Krigger, director of the Virgin Islands State Historic Preservation Office, expressed qualms. “A colonial military fort (which had also served as a police station and jail) was not the space for telling the story of our Native Americans,” he said.

When the Turnbull Regional Library in Tutu was completed in 2013, many had hopes that artifacts found in Tutu in 1990-1991 (and then those found near Market Square in 2014) could be displayed there. But the roof, which needed replacement within a year, has continued to leak, raising questions about the quality of the site for historic preservation.

Some have suggested that the Enid M. Baa Library near Market Square would be a good site for displaying artifacts from the territory’s Saladoid-Taino collection, but Krigger said legislation was passed to use the Baa Library to house the territory’s archives that largely consist of records and papers requiring special conditions for preservation.

The best hope now, according to Krigger, are two historic buildings near Government Hill.

More than 20 years ago, “a very generous bequest” was made to the territory for the purpose of building a museum in downtown Charlotte Amalie, according to Krigger.

Gregors Malling-Holm, born on St. Thomas around 1918, had “a great appreciation for cultural heritage in the Virgin Islands and acquired two properties near Government Hill which he gave to the territory for a museum,” Krigger said.

One of the buildings (once the site of the Parkside Restaurant) is located along the western side of Roosevelt Park. Plans were drawn for renovations, including a laboratory and a new wing to house the collection of artifacts. The two buildings are historic structures, and the desired renovations included climate control and security features as well as modernizing the plumbing, electricity, etc. When the project went out to bid, the proposals far exceeded the bequest, Krigger said.

According to Krigger, the territorial government still owns the buildings, and DPNR is still charged with building a museum. Several years ago, he noted, DPNR did apply for a grant to fund the renovation, but its application was denied.

“If the government can propose another site, we can explore another option,” said Krigger.

“A large space is necessary for storage of the government’s very large collections from numerous archaeological and historic sites, in addition to displays of selected items,” said Lundberg. “Such facilities are needed on St. Croix and St. John, as well as St. Thomas.”

The Historic Preservation office agrees.

“The management and long-term curation of the territory’s museum and research collections are two of the most critical issues facing the USVI today,” according to a state preservation plan prepared by the VISHPO with the assistance of the University of Alabama Museums’ Office of Archaeological Research.

The five-year plan (2016–2021) is being updated, according to Krigger, but it stands as the agency’s blueprint until a new version is published.

According to the report, “artifacts, scientific samples, and associated project data from the numerous research and cultural resource management projects that have taken place in the USVI are stored in variable and less than ideal conditions.”

Throughout the report, the authors cite the laws mandating the proper handling of historical artifacts in the custody of the Historic Preservation Office and acknowledge their challenges.

“Like many other government agencies, the VISHPO struggles to fully enforce its enabling legislation and regulatory decisions due to a lack of funding, limited governmental support, and insufficient staff. The VISHPO and its staff are primarily supported by the federal funding offered by the Department of the Interior’s NPS, although the GVI provides for staff and offers institutional support,” the report states.

The report includes a list of goals, including securing more funding from the V.I. Legislature.

So, where exactly are the artifacts now?

Material recovered from the two sites described in this series is in the government’s possession, but Krigger said he’d prefer not to disclose its whereabouts. Those collections, plus most of the government’s other archaeological collections, are in long-term storage with other government property. Additionally, some Virgin Islands artifacts that were not collected during government projects are held in private collections. All await facilities that are adequate for safe storage, preservation, and public display.