Once upon a time — actually, within the memory of many Virgin Islands residents — the Tutu Park Mall did not exist on St. Thomas.

The island’s first major indoor mall project had been announced with great fanfare in the mid 1980s, but it wasn’t until 1990 that bulldozers arrived on the five-acre site to prepare it for construction.

Then on Sept. 20, 1990, an environmental officer with the Department of Planning and Natural Resources came upon an astonishing discovery while making a routine inspection of the site: two partially exposed human skeletons accompanied by a wide scatter of prehistoric artifacts.

Recognizing the importance of his findings, Tom Linnio, the officer, immediately contacted Elizabeth “Holly” Righter, senior state archaeologist for the Virgin Islands.

“The site offered an unprecedented opportunity to study the remains of an entire prehistoric village and to document house types, village structure, and related sociocultural patterns,” Righter wrote.

For an archaeologist, the finding was beyond thrilling.

“This type of research had never before been conducted in the Virgin Islands,” Righter wrote in her 2002 scholarly book, “The Tutu Archaeological Village Site.”

But Righter knew she faced an enormous problem. “The site was in imminent danger of complete destruction,” she wrote.

At that time, the territory had no Antiquities Act to preserve unmarked burial sites or archaeological resources. (Although it had been proposed in 1983, the V.I. Legislature didn’t pass the Virgin Islands Antiquities and Cultural Properties Act until 1998.) Also, because the site was located a mile inland of the nearest coast, it was beyond the bounds of protection under the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1978.

Furthermore, the land was privately owned, and “There was no federal funding and ostensibly no requirement for federal permits that would have triggered compliance under Sec. 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966,” Righter wrote.

By law, there was nothing to obligate principal developers William Mahaffey and John Foster to halt construction, set aside any part of the site for preservation, or do anything about the important archaeological findings that were emerging from the dirt.

Enlisting the assistance of Alan Smith, then commissioner of the Department of Planning and Natural Resources, Righter mobilized the Historic Preservation Office (then known as DAHP) to begin negotiations with the developers. As they accepted the importance of the discovery, the developers agreed to grant researchers access to the property and postpone construction for three months.

Righter immediately called upon St. John-based archaeologist Emily Lundberg to serve as research associate. The two got to work — often in the pouring rain — hauling necessary archaeological tools and supplies in their backpacks.

As they looked upon the piles of disturbed earth, Righter and Lundberg wondered if everything significant had already been destroyed. “We were feeling kind of pessimistic,” said Lundberg. “We hoped that there was more further down. Holly put together a plan, and we started uncovering artifacts.”

Then, something of a miracle took place. Word of their discoveries was made known in local media; a flurry of activity mushroomed into a vibrant collaboration among government agencies, private businesses, community members, and experts from the around the world.

Community Rallies as Excavation Ramps Up

The effort began as land surveyors Travis Gray and Humphrey Ongondo of the Campbell Design Group, St. John, volunteered to lay out a framework for a grid that facilitated the mapping of the entire site using computer technology.

Chris Shearman and Associates contributed supplies, and Doug White and Tom Linnio set up a water screening system that made it possible for hundreds of volunteers to assist in the search for artifacts.

Volunteers with the St. Thomas Historical Trust, The Rotary Clubs of St. Thomas, the Environmental Association of St. Thomas, the Boy Scouts, the Girl Scouts, and other groups started showing up to sift through the dirt, often after school or work and on weekends. Groups of schoolchildren came to watch their progress during the day.

“Citizens, concerned about the imminent loss of the site to shopping mall construction, formed an ad hoc committee of businessmen to support the project,” Righter wrote.

The project was growing, and the researchers needed money to continue. Doug White of the St. Thomas Historical Trust joined architect Chris Green and associate Gail Choat to launch a fundraising campaign; soon, local businesses started hosting fundraising events.

The V.I. National Guard donated and erected a field tent, and the Antilles School provided a shipping container for a makeshift field laboratory. Joyce Craig of VITELCO arranged a $10,000 grant that covered transportation and lodging for a team of visiting archaeologists with the National Park Service.

The deadline for construction was repeatedly postponed, and in the 15 months following the discovery of the site, activity reached a peak.

“As the number of visitors to the site increased, daily tours were offered for a small fee,” Righter wrote. “Tour guides were volunteers who devoted many long, hot hours to trekking across the site in the hot sun, and explaining the procedures to the awed public.”

Local television stations made documentary films. Douglas Ubelaker of the Smithsonian Institution trained volunteers on the proper methods for excavating human burial sites. Ricardo Alegria, “the father of Puerto Rican archaeology,” visited the site.

Hotels, car rental companies and restaurants donated their services, funding the expenses for archaeologists and anthropologists from Puerto Rico, the United States and Europe to work on the project.

Experts in Caribbean archaeology, zooarchaeology, paleopathology and paleobotany established standards for the recovery of samples. They set up systems to register specimens and preserve artifacts that required special care; grants for material analysis followed.

“In total, after a series of three- to four-month deadlines, the fieldwork for the project extended to 11 November 1991,” Righter wrote. “Before the project ended, volunteers assisting with data collection and analysis had included 30 professional archaeologists, five physical anthropologists, ten graduate students, three land surveyors, numerous other anthropologists and scientists in their fields, and more than 500 members of the community.”

Ultimately, the total amount of site excavation far exceeded what would have been required if the site had been covered by federal or local preservation legislation, Righter concluded.

So what did all these experts and volunteers find at the Tutu site? Stay tuned for Part 2.

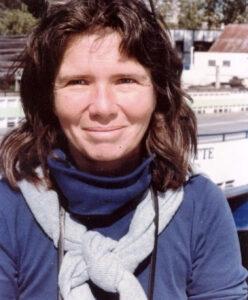

Editor’s Note: The Source is looking for photos of Elizabeth “Holly” Righter, the former senior state archaeologist for the Virgin Islands who died in 2011. Please email visource@gmail.com if you have one to share.