The U.S. Supreme Court Monday dealt a blow to advocates of birthright citizenship for territory residents and to efforts to overturn the so-called Insular Cases, the blueprint for U.S. relations with its overseas territories.

As is typical when it denies a petition to hear a case, the Court did not issue any explanation for the denial, nor did it reveal whether the decision was by majority vote or unanimous.

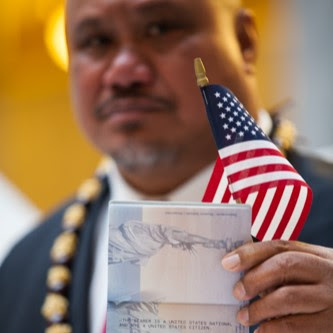

In the case known as Fitisemanu v United States, the Southern Utah Pacific Islander Coalition and three American Samoan nationals (John Fitisemanu, Pale Tuli and Rosavita Tuli) living in Utah sought to establish a right to U.S. citizenship under the 14th Amendment to the Constitution.

They won the case in a lower court in Utah but lost in an appeal to the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals. With the Supreme Court refusing to hear the case, the Tenth Circuit decision stands.

A major complication for proponents was the fact that the government of American Samoa actually opposed the Fitisemanu petition, arguing birthright citizenship could be more harmful than beneficial to American Samoans.

Residents in American Samoa are considered “nationals.” Those in Guam, Puerto Rico, the Northern Marianas and the U.S. Virgin Islands are U.S. citizens, but that status is by virtue of an act of Congress, not as a constitutional right.

“Our case is over,” Neil Weare, president and founder of Equally American, said Monday after the Supreme Court released its decision. He had attempted to use the Fitisemanu case as a vehicle for revisiting the Insular Cases.

Both Justice Neil Gorsuch and Justice Sonia Sotomayor had signaled in written comments on previous cases that they were open to a review of the Insular Cases and Weare said some “court watchers” viewed the Fitisemanu case as a “once in a generation opportunity” to make that review.

The fact that the Court backed away from the case shows “just how challenging” it is to fight for equal rights for people living in the territories, he said.

The Insular Cases – a series of Supreme Court decisions made in the early 1900s after the U.S. began acquiring lands outside the continental U.S. – have been criticized for blatant language within them that reflects racist attitudes of the times and for treating residents in the newly established territories with fewer rights than stateside residents.

The Fitisemanu case garnered considerable attention. There were numerous “friends of the Court” or amicus briefs filed in support of the petitioners by prestigious groups and individuals who argued that the system established through the Insular Cases is discriminatory and unfair. Filing supporting briefs were:

- Scholars of Constitutional Law and Legal History (law professors identified as “scholars who have extensively studied the constitutional implications of American territorial expansion”)

- Descendants of Dred Scott (the infamous Dred Scott case inspired the 14th Amendment as a way to guarantee citizenship regardless of race)

- The American Civil Liberties Union

- The Samoan Federation of America, Inc.

- The Virgin Islands Bar Association

- Current and former elected officials of Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands (The V.I. members of the group were Congressional Delegate Stacey Plaskett, former governors John P. de Jongh and Kenneth E. Mapp, and former delegate Donna M. Christian-Christensen.)

- Citizenship Scholars (a number of individuals teaching law, history and political science at various universities)

- Former federal and local judges (from the V.I. are Adam G. Christian and Soraya Diase Coffelt)

Opposition to the petition, besides that from the government of American Samoa, came in a brief filed by the Northern Marianas Descent Corporation and United Carolinas Association, both of which are described as “nongovernmental organizations dedicated to the protection and advancement of the interests of the indigenous peoples of the Northern Mariana Islands.”

Both of the organizations “are dedicated to protecting the existing restriction on acquisition of land in the Northern Mariana Islands to persons of Northern Marianas descent, a restriction that has been upheld on the authority of the Insular Cases.” That restriction might be threatened by full citizenship since it could conflict with federal “equal protection” statutes.

American Samoa also restricts property rights to natives.

In its motion to intervene in the Fitisemanu case, the government of American Samoa wrote, “For 3,000 years, on an archipelago 7,000 miles from this Court, the American Samoan people have preserved fa⸍a Samoa – the traditional Samoan way of life, weaving together countless traditional cultural, historical, and religious practices into a vibrant pattern found nowhere else in the world.”

The unique relationship it formed with the U.S. has been in place for more than a century, and now the Fitisemanu petitioners seek to disrupt it, the government said.

The petitioners “would love to claim that their stance serves the interests of the American Samoan people,” it said, but those people don’t share that view. “The American Samoan people have not yet reached consensus on whether to accept the privileges and responsibilities of birthright citizenship – but they firmly believe (that decision) should come through the democratic process, not through a judicial misreading of the Citizenship Clause.”

Further, the American Samoan government’s motion to intervene said, “Nothing prevents petitioners from seeking citizenship for themselves through the streamlined naturalization process that Congress has provided for persons born in American Samoa.”

When it made its determination against Fitisemanu, thereby reversing the lower court, the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals said that the objections from the government of American Samoa had “not been taken into adequate consideration” by the lower court.

Because the Supreme Court did not specify the reason for its decision not to take up the case, it is not clear what role, if any, those objections played in its decision.

“It’s hard to know what the justices thought,” Weare said. “It’s hard to guess what their reasoning was.”

Whatever it was, “We’re going to continue fighting in the courts and in Congress,” he said, adding that Plaskett has already used her position as the Virgin Islands congressional delegate to urge Congress to dismantle the Insular Cases. “The fight goes on.”