Every year, I get calls from both private and public schools to give presentations about Virgin Islands history. Today, children can gather in classrooms or any other setting to learn to read, write, etc., and be educated formally or orally by their parents, grandparents and great-grandparents about the natural and cultural history of these islands.

Almost 300 years ago in the Danish West Indies, children as well as adults didn’t have the privilege to learn to read and write. It was well known historically that most planters of the Danish West Indies were against having any form of slave-gathering. There were also Danish laws that prohibited the gathering of slaves on plantations. These laws imposed fines and penalties on planters who allowed their slaves to have such meetings or gatherings on their plantations.

Nonetheless, the Royal Archives of Denmark also revealed that there were ordinances that made the exception to the laws to allow slaves to attend Moravian schools or gathering of meetings. In 1732, the Moravian Brethren began their effort to teach enslaved children to read and write so that they could read the Gospel for themselves. In fact, on June 8, 1839, King Frederik created a school system for Black slaves by giving Gov. Gen. Peter von Scholten permission to travel to Herrnhut in East Germany to negotiate with Moravians to establish country schools in the Danish West Indies.

The Danes created an educational system for children of slaves, mulattoes, and “free Blacks,” making the education system for the enslaved population during the latter part of slavery in the Danish West Indies one of the best in the West Indies. Cornelius was a product of this free education system. He was born a slave on the island of St. Thomas. His mother was one of the first members of the Moravian congregation on St. Thomas. In 1740, his mother was baptized in the faith and was named Benigna after Count Zinzendorf’s daughter, who was instrumental in establishing the Moravian Church on the Danish islands.

Like his mother, Cornelius was baptized by Bishop Johannes in 1749. He worked as what was known then as a “National Helper” for the Moravian mission. The brethren of the church described Cornelius as well liked and a reliable person, well respected in his community with good manners, which set an example for both whites and Blacks. According to Oldendorp, a Moravian missionary, Cornelius was a talented slave, and a first-class mason who laid the foundation stones of six Moravian churches on the islands.

The six churches Cornelius laid the cornerstones for were: Friedensthal on the outskirts of Christiansted; New Herrnhut (Posaunenberg) on St. Thomas; Bethany near Cruz Bay on the west side of St. John; and Nisky outside of Charlotte Amalie where the Moravian Brethren acquired land at Krum Bay not far from Mosquito Bay where the Cyril E. King International Airport is located today. The other two churches were Friedensberg on the outskirts of Frederiksted town; and Emaus at Coral Bay on the east side of St. John, not far from where the slave insurrection began in 1733. These churches still stand today, a testimony to a slave’s will to become a free man.

Cornelius was also a powerful preacher of the Gospel, which moved even the white Brethren and Sisters into tears. His wife, Barbara, was also a faithful member of the church. He was not only a master mason, but he could also read and write Creole, Danish, Dutch, German, and English. In 1767, Cornelius was a free man and had bought his wife’s freedom and later that of his children before he bought his own.

In a letter Cornelius wrote to Ernst von Schimmelmann, the largest slave owner in the Danish West Indies with estate holdings on all three islands, he offered cash to purchase his grandchild Johanna her freedom. Beside escaping as a maroon or runaway slave, buying one’s freedom was another way out for the enslaved. However, many slaves didn’t have the opportunity to purchase their own and their family’s freedom. It was a costly affair, and craftsmen like Cornelius had the best possibilities to save money and purchase their freedom.

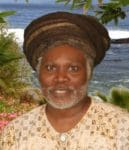

The story of Cornelius is fascinating. It is a true Virgin Islands story where a slave purchased his freedom and rose to the occasion of greatness. He was known as “The Black Evangelist” of his day in the Danish West Indies and in Germany. There is a portrait of Cornelius in a museum in the Moravian Archives in Herrnhut, East Germany. It was Thomas de Malleville (1739-1798), the first native-born governor of the Danish West Indies, who came up with the idea of a portrait of Cornelius.

Malleville was converted to the Moravian faith by Cornelius, his good friend. That said a lot about Cornelius as a man, and from a slave to a free man. The painting of Cornelius was presented in 1783 to the Moravian headquarters in Herrnhut by Malleville. There is a lot more to say about the brother Cornelius story. Nevertheless, it is this historical information that our children should learn that would inspire them to greatness. Despite Cornelius’ consequences as a slave, he rose to the occasion to educate himself and thousands of others in the Danish West Indies.

As a community, we should encourage our children never to give up on their education. Cornelius’ story is one that they can learn from. Virgin Islands history didn’t begin yesterday. Virgin Islands history are all we.

– Olasee Davis is an Extension Professor/Extension Specialist in Natural Resources at the University of the Virgin Islands who writes about the culture, history, ecology and environment of the Virgin Islands when he is not leading hiking tours of the wild places and spaces of St. Croix and beyond.

![Detail of oil painting (courtesy of Jon Sensbach) held by the Moravian Archives (Unity Archives [Archiv der Bruder-Unitat]), Herrnhut, Germany). Cornelius was born in the Danish Virgin Islands of African parents. He ultimately became a Moravian and a prominent elder](https://stthomassource.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2022/03/Cornelius-211x300.jpg)