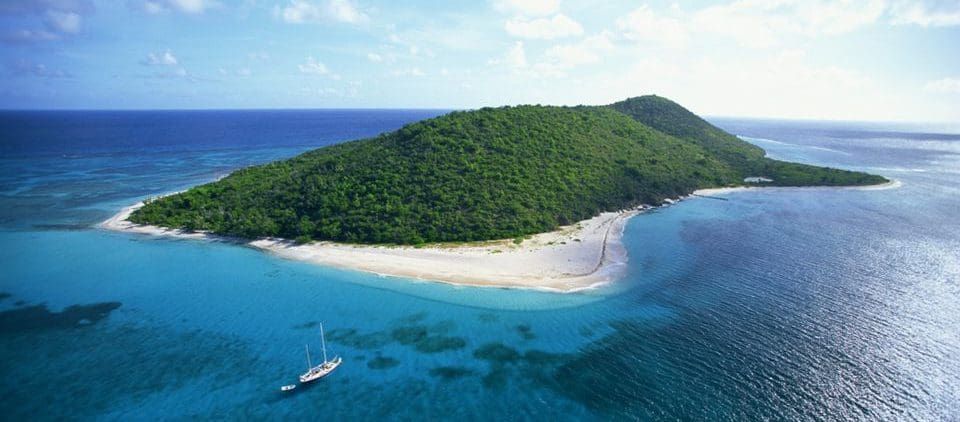

This article is as relevant today as when I wrote it a few years ago, stressing how important it is to establish open green spaces in the Virgin Islands if we want to grow a healthy economy. Why do you think people flock to these islands every year by the thousands? Despite the pandemic that impacted our local economy, people are still flocking to these islands. Believe me, it is none other than the natural beauty, history, culture, and exploring the underwater marine gardens that surround the Virgin Islands coastlines that attract visitors.

What inspired me to write this article a few years back was a PBS series on the birth and establishment of national parks in the United States. Religiously, I sat down and watched the series titled “The National Parks: America’s Best Idea.” What a treasure we have as Americans. I believe our greatness as Americans is not so much in our military strength, but in embodying nature by creating parks that remain a refuge for the human spirit. It was at Yosemite that the birth of our national parks began 150 years ago. Yosemite is a place of awesome natural beauty and cultural wonder.

The Native Americans, particularly the Ahwahneechee Indians, occupied the area we know today as Yosemite for thousands of years. As the first white settlers spread across America’s landscape, driving out Native Americans from their home, Yosemite was rediscovered in 1851. A young doctor named Lafayette Bunnell, as the story goes, was struck by the natural beauty of Yosemite. He and others entered Yosemite Valley searching for Indians with the intention to drive them out of their homeland.

Bunnell was so taken aback by the natural wonder and beauty of the place he called it, mistakenly, “Yosemite,” believing it to be the name of the Indian tribe that lived there. In 1855, a second group of white settlers entered Yosemite Valley. This time, they were led by James Hutchings. Hutchings took photographs and the news and images quickly spread, bringing more tourists to the area. In those days, to visit Yosemite you either went on foot or on horseback, which took several days.

When Frederick Law Olmsted, the one who was responsible for designing New York City’s Central Park, visited Yosemite, he wrote of “the greatest glory of nature … the union of the deepest sublimity with the deepest beauty.” However, there were growing concerns that Yosemite needed to be protected legally if the area was to remain in its natural virgin state.

A bill was introduced to Congress, which was unprecedented in America at that time, to set aside large tracts of natural scenic land for the enjoyment of every American. In 1864, President Abraham Lincoln signed into law an act of Congress granting the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias and Yosemite Valley to the state of California. Today, Yosemite is a national park.

Then, toward the end of the 19th century, a young politician who later became president of the United States, championed the cause to protect some of America’s greatest natural landscapes. Yes, it was President Theodore Roosevelt, who during his presidency created five new national parks, 18 national monuments, 51 federal bird sanctuaries, four national game refuges, and preserved more than 100 million acres of forest.

As I sat there, night after night, and watched the series explain how America’s parks were established night, it dawned on me that the Virgin Islands has no territorial park system of its own established, except on paper. What a damn shame! We boast so much about our tourist economy with little regard to the protection and preservation of scenic beauty. On St. Thomas, we are building on every inch of land, putting its natural beauty in jeopardy. Most of our political leaders have no sense of direction when it comes to selling these islands as a tourist destination.

It took outsiders, like Arthur S. Fairchild’s gift of Magens Bay in 1946, and Laurance S. Rockefeller’s gift of the St. John National Park in 1956, to give the people of these islands some of the best natural and cultural landscapes of the Virgin Islands. When Rockefeller purchased over half the land area of St. John in the early 1950s, it had a negative effect within the territory. The size of the area and the scale of the gift provided an excuse to those in and out of government who thereafter saw little need for setting aside any land for a park.

We are also indebted to Fairleigh Dickinson for the large parcel of land north of Isaac’s Bay on St. Croix’s East End and to David Vialet for his gift of Cass Cay at the False Entrance to the St. Thomas Mangrove Lagoon. Later on, the Paiewonsky brothers, Ralph and Isidor, donated most of Hassel Island for inclusion in the Virgin Islands National Park. Within 90-plus years of being an American territory, there are no appointed governors or elected governors who see the importance of establishing a territorial park system in the Virgin Islands.

St. Thomas is now reaping the fruit of unplanned development. And yet, you would think some governor would rise to the occasion of protecting and creating open green space, seeing that it is connected to the tourist industry. I can only think of the late Cyril E. King who had the vision to envision a Territorial Park System, but he died in office before it ever came to fruition. King was in negotiation with the Rockefellers to protect the northwest of St. Croix.

It is sad, very sad, that the dreams of such a great man with such a vision for these islands never came true regarding setting aside scenic natural beauty for the people he loved. I am still hopeful that the northwest of St. Croix, including Annaly Bay, Wells Bay, Wills Bay, Sweet Bottom Bay, Maroon Ridge, Bodkins Mill, and Estate Hermitage and Parasol Mill, will become a territorial park for the people of these islands. These lands hold astonishing scenic beauty. National parks are spiritual places. Why can’t we see that in the Virgin Islands?

Olasee Davis is an Extension Professor/Extension Specialist in Natural Resources at the University of the Virgin Islands who writes about the culture, history, ecology and environment of the Virgin Islands when he is not leading hiking tours of the wild places and spaces of St. Croix and beyond.