Underwater robots that use machine learning to teach themselves how to think like a diver who’s exploring a coral reef.

Computer models revealing swirling tides and currents that may show why marine life thrives at one particular spot and not at another.

Underwater listening devices that detect the sounds of healthy reefs alerting scientists when marine life becomes endangered.

These are just some of the cutting-edge technologies being tested in the waters of St. John several weeks ago by researchers from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, better known as WHOI.

The team of 21 WHOI scientists and students were based at the University of the Virgin Islands’ marine lab at Lameshur Bay on St. John. The lab, originally built in the 1960s, is now part of VIERS – the Virgin islands Educational Research Station – a rustic conference center for youngsters to learn about the environment and for marine scientists to conduct serious work.

Most of VIERS’ facilities were destroyed by Hurricane Irma in 2017, but the old marine lab, rebuilt in 2006 by the University of the Virgin Islands and the National Science Foundation, still stands.

Earlier in November, it was humming with activity as researchers took advantage of the relatively calm tropical waters to see exactly what their devices could do.

Among them was microbial ecologist Amy Apprill, the team leader for WHOI’s Reef Solutions, a multi-disciplinary initiative developing new technologies to monitor reef dynamics and health as well as intervention tools. With coral reefs around the globe dying at alarming rates, the initiative’s goal is to protect reef ecosystems from the effects of climate change and, with some good luck and science, even reverse some of the damage.

Aran Mooney, whose work the Source featured last November, was back on island refining his listening devices which record the “snap, crackle and pop” sounds of a healthy reef – plus an occasional high-pitched “whoop” of a passing humpback whale.

This year, researchers were also analyzing water samples from Mooney’s six sites on the south side of St. John, using syringes with attached filters to collect microbes.

“Each reef habitat has a unique microbial signature,” said Apprill. “We can look at the microbes –using molecular biomarkers – to tell what species are there.”

The molecular biomarkers are also being analyzed to find the cause of stony coral tissue loss disease, a disease which has devastated brain corals, star corals and other major reef-building species in the Virgin islands since 2019.

Apprill and colleagues from the University of the Virgin Islands are honing in on the microbes that may be leading to the corals’ mortality and are looking closely at around 20 possible pathogens. With 10 million microbes in 20 drops of water, narrowing the range of possibilities is a challenge.

Meanwhile, marine chemist Colleen Hansel, who invented DISCO, an instrument to examine coral stress markers non-invasively, was field-testing a “vitamin mixture” for corals.

Hansel is one of a group of scientists working on developing the materials used to build artificial reefs. “The goal is to make growth substrates that will provide an immune/growth boost to larvae that land on degrading reefs – making restoration efforts more successful,” according to a WHOI press release.

Jeff Coogan, an engineer at WHOI, was testing out ceramic tiles (made with aragonite and trace metals) on which to grow corals in laboratories or in the sea. Coral larvae like to grow along edges, so tiles with grooves in different patterns were being studied.

To determine which materials and designs work best, Nadège Aoki, a graduate student in a joint program between WHOI and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, was busy peering into a microscope to identify and count the tiny creatures growing on the tiles.

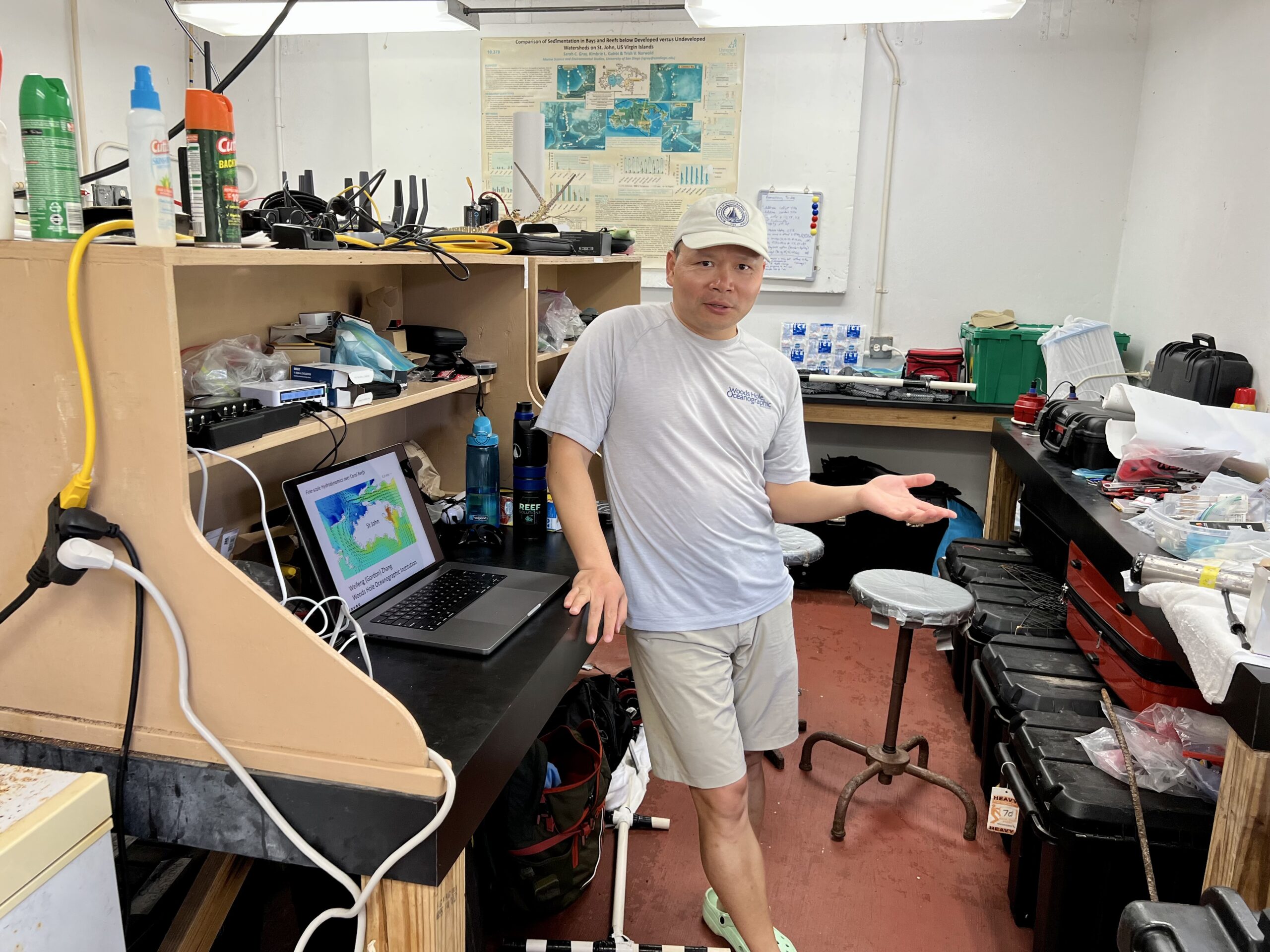

While some researchers were looking at the microscopic picture, others were taking in a much wider view. Among them is Weifeng Gordon Zhang, who studies how water flows around reefs.

Zhang displayed samples of his computer models, which show how the temperature, salinity, and currents fluctuate around St. John. His models show that the water on the north shore has more salinity and current flow than the south side of the island.

In 2021, researchers seeded the south shore of St. John with coral larvae, and Zhang recorded their dispersal pattern. The data, combined with Mooney’s reef soundscape detection technology and the research on the best possible substrate for growing coral, can lead scientists to make use of the best conditions for growing corals in natural conditions.

The information can also lead to understanding how coral diseases spread or why sargassum seaweed piles up on certain beaches.

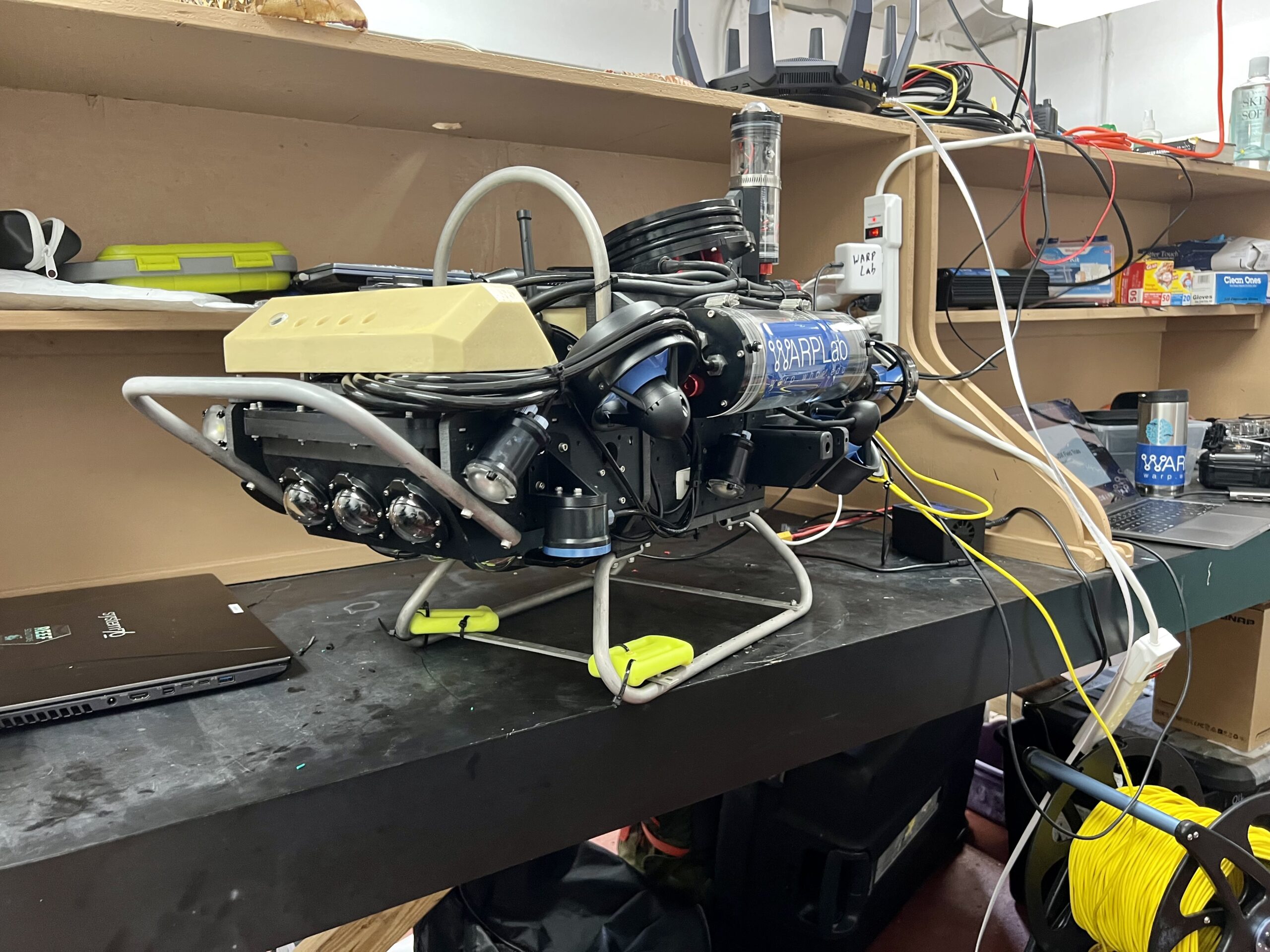

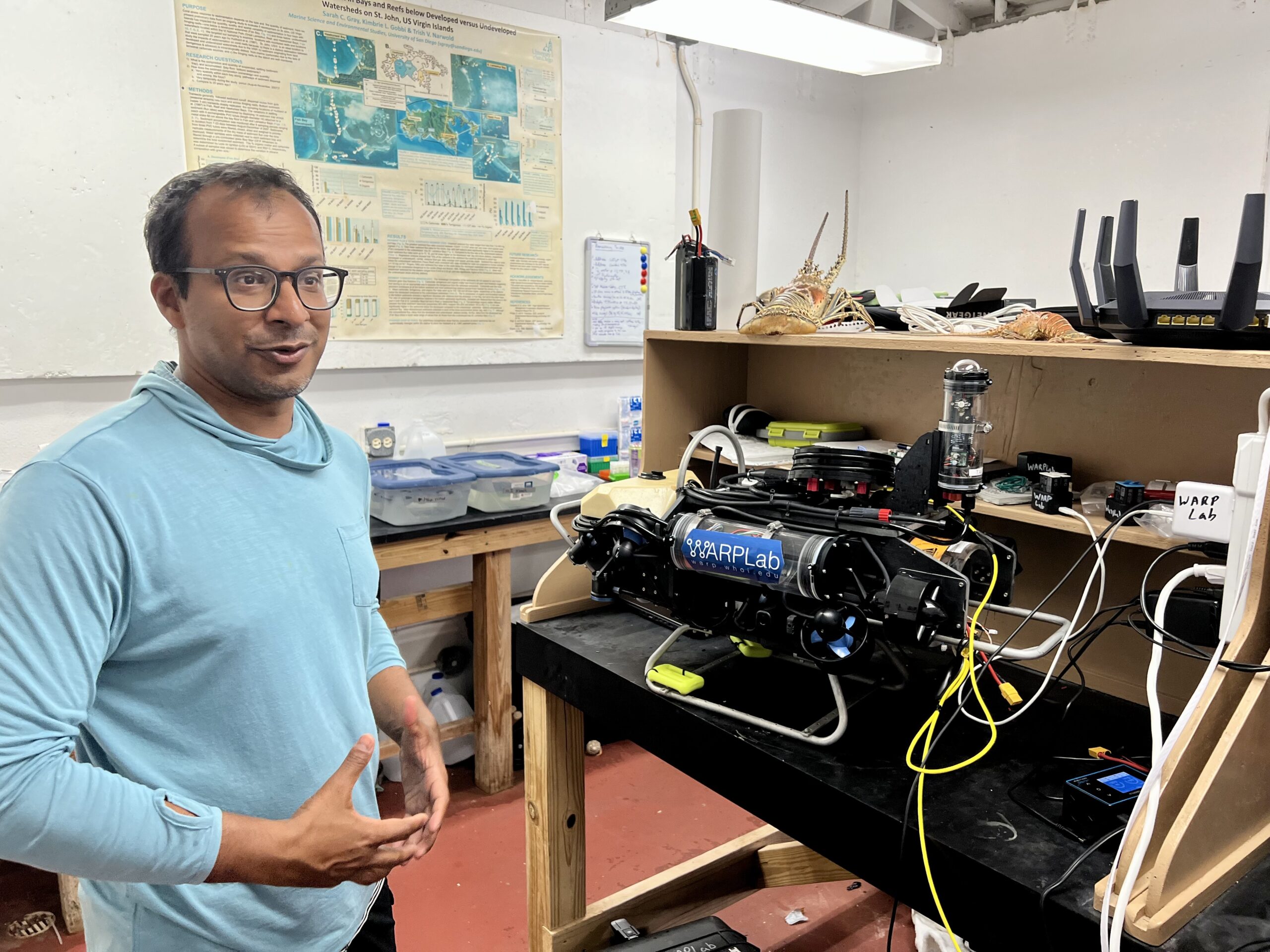

Perhaps the coolest device being tested – at least from the general public’s point of view – is an underwater robot known as CUREE, which stands for Curious Underwater Robot for Ecosystem Exploration.

Yogesh “Yogi” Girdhar, a computer scientist at WHOI, has designed the robot to gather visual data from CUREE’s cameras and combine it with data from Aran Mooney’s devices to find patterns in reef habitats.

“CUREE is autonomous – no one has to pilot it.” Girdhar said. The robot has tracking capabilities and can follow a fish for a long period of time, monitoring what it eats and where it goes.

Right now, Girdhar is trying to get the robot to learn the proper distance for tracking a fish and when to turn off the battery to minimize the disturbance to marine creatures and conserve the amount of time that CUREE can operate without recharging.

The device is a work in progress. “Coral reefs are the most complex ecosystems,” Girdhar said. “The goal is to make it adaptable to study marine animals in many environments” and then get it ready for production and distribution around the world.

All of the ongoing research has a direct benefit to marine scientists working locally at the Nature Conservancy and the University of the Virgin Islands.

Marilyn Brandt, a UVI researcher who has been focusing on coral diseases, is collaborating with Amy Apprill and Colleen Hansel to manage a $740,000 federal hurricane recovery grant to study coral growth and develop methods of reef resilience.

Some of the work will focus on artificial reefs. “It’s not so much that artificial reefs should replace natural reefs, but there’s an interest in integrating them to jumpstart rehabilitation and serve as havens while natural reefs are recovering from things like hurricanes,” Brandt said. “We want to create refuges for fish after a storm.”

Click here for a short video that shows more about WHOI’s coral research, including the deployment of the underwater robot.